Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is critical for the future of aviation. In the UK, there is now a SAF Mandate, requiring an increasing share of the UK’s aviation fuel to be sustainable over the coming years. The Government has also introduced primary legislation to enable a SAF Revenue Certainty Mechanism; this article explains the importance of this policy and what it means for the development of the sustainable fuels and aviation industries.

Aviation is one of the hardest sectors of society to “decarbonise” – shorthand for reducing its climate change impact. Although global aviation accounts for only 2-3% of human-generated emissions, its share is expected to grow as other sectors reduce. Furthermore, 80% of the world’s people have never flown; as economies develop, demand for air travel increases, while at the same time, along with every other sector, net greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced to zero.

IATA estimates that SAF will contribute [over 50%] of this reduction. Hydrogen and electric planes have limited range, and would require a complete change of the fleet and refuelling infrastructure. They will play their part in the future, especially in short journeys with small aircraft, but SAF is the only fuel solution available at scale now, and is critical to decarbonising long-haul flight; 73% of aviation’s CO2 emissions come from flights over 1,500 nautical miles. SAF is a drop-in replacement for conventional jet fuel, and most types of SAF can be used at up to 50% in a blend with standard jet fuel, in any commercial aircraft worldwide. It burns in the same way as jet fuel (although generally with lower soot emissions due to small differences in chemistry), but over the carbon lifecycle it is sustainable, because it is made from renewable or waste carbon sources. Today, almost all SAF is made from vegetable oils, of which there is a limited supply, but the technologies already exist to make it from a much wider range of carbon feedstocks, thus unlocking the supply that will be needed ultimately to meet jet fuel demand without the extraction of fossil fuels.

Velocys, a member of TVCC, is a supplier of chemical conversion technology known as the Fischer-Tropsch process, which is at the heart of one of the most important ways of making SAF. It can be used in combination with other technologies to convert a wide variety of feedstocks, including municipal solid waste, forestry wastes such as bark and branches, or agricultural residues, into SAF. The basic process is illustrated in Figure 1. It can also be used for so-called e-fuels or power-to-liquids fuels, where the only carbon source is carbon dioxide, and the energy is supplied from renewable electricity via electrolysis of water to hydrogen. Velocys has been leading the development of the Altalto waste-to-SAF project in the Humber region, which already has planning consent and is one of the most advanced waste-to-SAF projects in the world. The individual technologies that will make up the conversion process are all proven at scale, so that technology risk is relatively low; however, there are as yet no operating waste-to-SAF plants, so the project (like most advanced SAF projects) is still classified as first-of-a-kind, which puts it in a different category for financing than a repeat project.

Figure 1 Waste-to-SAF Process

SAF is more expensive to make than fossil jet fuel today. In order to encourage its uptake, the UK has introduced a SAF mandate, thus providing a demand signal. Tradeable “SAF Certificates” are issued to suppliers of SAF, which are then sold, directly or indirectly, to fossil fuel suppliers, who are obliged under the SAF mandate to obtain such certificates (or if they cannot, to buy out their obligation). The buy-out price is sufficiently high that it in most cases it will be cheaper to purchase SAF than to buy out.

However, although the SAF Mandate creates an economic incentive for SAF production, it does not on its own make SAF projects bankable. As with any infrastructure project, banks require confidence that the debt will be serviced, and a major component of that is certainty of price. The SAF Certificate market is new, so there is no price history to support hedging; equally, the purchasers of SAF Certificates (airlines, fossil fuel suppliers or traders) are generally not prepared to take the risk of being out of line with the market.

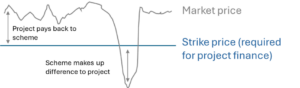

To help address this problem, the Government plans to introduce a SAF Revenue Certainty Mechanism (RCM), similar to the Contracts for Difference that have been highly successful in stimulating Britain’s wind power industry. Under such a contract, a strike price, sufficient to service debt and provide a reasonable return to investors, is agreed between the project company and a Government-backed entity such as the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC). Under the contract, if the market price (the price which the project has obtained by selling its SAF to airlines, fossil fuel suppliers or traders) is lower than the strike price, the scheme makes up the difference; if the market price is higher than the strike price, the project pays the difference back to the scheme, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Revenue Certainty Mechanism

The scheme’s creditworthiness is assured by the backing of the Government; however, the intention is that it should have no net cost to the taxpayer, therefore a levy on fossil fuel suppliers (thus ultimately falling upon the airline passenger or cargo user) is envisaged, in order to build up a fund for the scheme, which may or may not be drawn upon (depending on market conditions).

Primary legislation for the RCM has been introduced to Parliament, but the detailed regulations that are needed for a functioning scheme are not expected to be enacted until late 2026. In the meantime, projects face something of a hiatus, since even such SAF offtakers as might be willing to take some market risk are understandably reluctant to do so now, given that a mechanism is due to be introduced next year.

Notwithstanding this delay, the UK has probably the most favourable SAF policy in the world, at least for the advanced biofuels made from solid waste feedstocks. The mandate has several important and unique features: firstly it includes an explicit element that can only be met by SAF made from such wastes. This recognises the importance of developing routes to SAF beyond the present vegetable oil conversion. Secondly, the mandate provides revenue that is proportional to greenhouse gas reduction, thus encouraging SAF producers to make their plants as efficient as possible, aligned with climate change goals. Thirdly, the explicit buy-out price, whilst it limits producers’ upside, has the effect of making very clear the cost of failure to meet the mandate, thus encouraging purchasing behaviour.

As a result of the SAF Mandate and other policies such as the Department for Transport’s Advanced Fuels Fund, a grant programme designed to support SAF projects during the development stages, the UK has several SAF projects in development. This is a new industry, enabled by technology, with the potential to create thousands of jobs, enhance energy security, dispose of waste in an environmentally beneficial way, and allow aviation to become sustainable. However, it is still a nascent industry, and all projects face challenges – securing feedstock, raising finance (due to the combination of novel technology and a new, regulation-driven market), securing utility connections, gaining planning consent and permits, and many others. To create a thriving SAF industry in the UK will require a high degree of collaboration and risk sharing throughout the aviation, chemical, energy and financial sectors, amongst others, together with steadfast support from government and civil society.

One remaining challenge not yet mentioned is also a big opportunity. SAF projects need to find and retain the skilled people required to build complex plants and bring them into safe, stable operation. Engineering is a critical part of the skill set, though by no means the only one. The Thames Valley has many skilled and experienced engineers, many of whom have gained experience while supporting plants based on oil and gas in other parts of the world. The prospect of a SAF industry provides exciting an exciting future for experienced and newly qualified people alike, with interesting jobs that will make a vital difference to the environment and to the future of humankind.

By Dr Neville Hargreaves